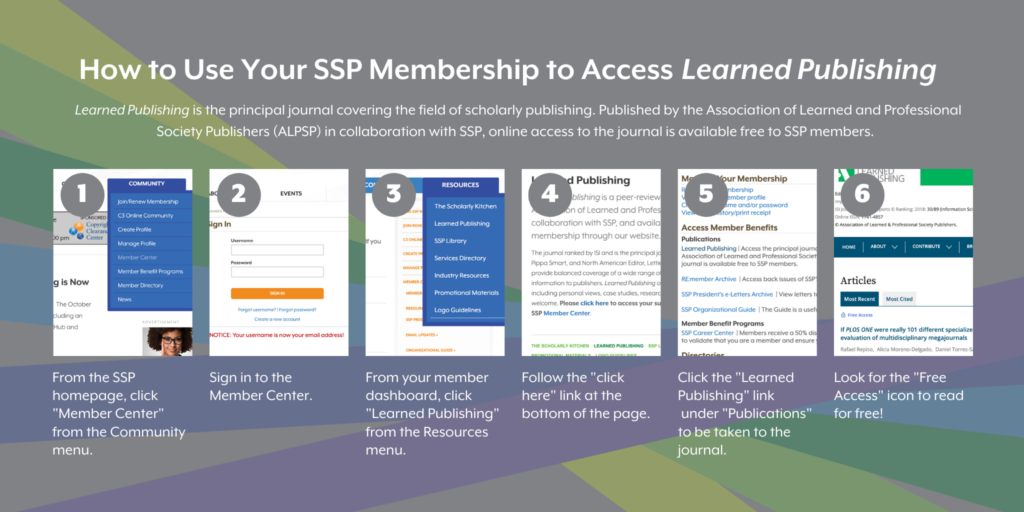

Now available as an Early View article of Learned Publishing. Access to Learned Publishing is a benefit of membership in SSP. You can read the full-text online.

Academic journals’ usernames and the threat of fraudulent accounts on social media

Adam Coates | Learned Publishing | Version of Record online: December 3, 2021

Adam Coates assessed the social media presences for 50 journals from the 3 core Web of Science indexes (SCIE, SSCI, and AHCI), to determine the prevalence of imposter social media accounts (that is, social media accounts designed to deceive users into believing the account is legitimate and run by the owner of the publication that is being imitated). By evaluating whether the journals in his sample had social media presences at all, and, for those that did, whether the same usernames were used across all platforms, Coates was able to identify factors that put journals at risk for becoming imitated by a fraudulent account. His paper further addresses the risks these fraudulent social media accounts can impose upon legitimate scholarly journals and their publishers and presents potential countermeasures publishers can implement to protect their journal assets and reputation.

The author told us a bit about how they came to focus on this topic:

What led you to take an interest in this area of research and to pursue this study?

The study essentially started from a suggestion by a colleague. He mentioned the idea that journals’ social media usernames might be open to exploitation if they are not verified. The topic seemed intuitively interesting because I could see how easy it might be to create a fake social media account for a journal.

When refining the focus of the study, it became clear that there was a gap at the intersection of research into academic deception and social media fraud. Importantly, most research into academic fraud focuses on describing the deception after it has occurred. When the study was conceived, I was unaware whether social media fraud in academia was actually happening, so it seemed interesting to develop a study that focused more on exploring the potential for deception rather than reporting deception that has already occurred.

Like you, I have come across my fair share of fraudulent journal social media accounts, with imposters posing as legitimate journals using social media handles and presences that are designed to mimic the legitimate journal to trick users. What is the potential type of harm can this type of fraud and misuse cause to legitimate journal publishers and their users?

Based on what I discovered, reputation damage is the main impact for the journals. The fraudulent social media accounts that I found were posting information that misrepresented the journal. For example, I found fraudulent accounts posting fairly strong opinions about COVID-19 and the previous US president. The replies to these posts suggested that at least some of the audience were deceived and they were responding with a low opinion of the journal.

More speculatively, fraudulent accounts can be used to deceive academics to steal their money. A fraudulent social media account can easily link to a website for a fraudulent conference, for example, and deceived academics might send conference fees to the fraudsters. I did not find any instances of this specific approach being used, but there are many examples of fake and predatory academic conferences so I think it is certainly possible.

In your paper, you briefly mention that verification for accounts is not an adequate solution to this problem. Can you expand on that for our readers?

Most social media networks provide account verification in which an employee of the social media company manually checks the identity of an account and a checkmark is added next to the account name. Although this system is designed to add a layer of trust, there appear to be two problems with relying on this approach to determine the legitimacy of a social media account.

The first issue is simply that journals do not seem to be using this verification system. In my research, only 15 of 41 social media accounts had been verified. This may be due to disinterest or unfamiliarity with the system.

The second issue is that even if journals do use verification, research has shown that most people do not pay attention to verification symbols when judging the validity of the information. It is suggested that as verification became increasingly common, it lost its value as a marker of trustworthiness. I would also suggest, for this particular context, because fraudulent academic social media accounts are a new and rare event, the average viewer of social media probably doesn’t consider the possibility that what appears to be the social media account of a journal is, in fact, a fraudulent account.

Do you feel journals without any social media presence are at an even greater risk for being imitated by these imposters?

This might depend on the goal of the imitation. Journal hijacking and fraud have typically targeted smaller journals, and this type of deception has financial motivation. Fraudulent social media might be discovered less quickly when a journal does not have legitimate accounts because the editorial board is less likely to be active on social media. The larger the network of the journal editors, the more quickly the fraudulent accounts might be found. This would suggest that journals without social media would be prime targets.

However, the fraudulent journal social media that I found were all mimicking larger journals that have a significant social media presence. But it might be considered that these fake accounts were only being used to spread misinformation. Furthermore, the accounts had only a small number of followers, and these were from the general public, so this might explain why they had not yet been discovered and shut down.

Taking this into account, essentially, I would suggest that journals without social media are more at risk for financially-motivated fraud, but since the type of fraud is more elaborate than fraud for spreading misinformation, it is likely to be less common.

Who are the primary targets of these types of fraudulent accounts, and what can legitimate publishers do to help combat the effects?

As mentioned, the accounts that I found targeted the general public and were spreading politically motivated information. The fake accounts would not be very convincing for an academic audience since they did not have links to the legitimate journal website and contained basic grammar and style errors, for example.

To address this type of fraud, the simplest approach publishers can take is to search for the journal name on social media occasionally. Upon finding a fake account, they may contact the social media platform to remove the account.

This was an important paper, and it will be interesting to see how the social media landscape may change in the coming years. What’s next on your research agenda?

My current main interest is how the research process is represented in writing. I plan to investigate the relationship between factors that influence the key decisions during a study and the write-up for that study.

The January issue of Learned Publishing is now available! The entire issue, including this spotlight, is available as part of your SSP membership!

News contribution by SSP member, Jennifer Kuhn. Jennifer is the Publications Director of Permanente Medicine.

Join the Conversation

You must be logged in to post a comment.